jeremy gavron, 'felix culpa'

If you’ve only heard the plot, Felix Culpa doesn’t sound strange at all. Jeremy Gavron’s new novella follows a nameless writer who plays detective. He’s investigating a teenage boy with the ironic name of Felix; ironic, because Felix recently left prison, travelled mysteriously to the ‘hills in the north’, and was found dead there in the snow. The prison where Felix was held, and where the narrator first hears his tale, is in a wet and dark city where everyone seems, like the narrator, to live in ‘a state of dull inertia’. We watch as our man trudges around, fishing for scraps about Felix’s life. As detective thrillers go, it isn’t the most thrilling, but its story is straight enough.

Felix Culpa, however, is less typical in that its novelist didn’t write it – he put it together. Each chapter is a chain of staccato phrases, broken into tiny paragraphs like this:

Steal bread under the cover of darkness.

Running monkey-like, bent double, over fences and through bushes.

Mud flying from his feet.

But Gavron didn’t coin these phrases; they belong (respectively) to Aharon Appelfeld, Amos Oz, and A.B. Guthrie Jr. In fact, ‘the great majority of the lines’ in Felix Culpa are taken from a hundred ‘sources’, as Gavron calls them, by eighty different authors. Flick to the bibliography, and you find it a place of hustlers and outcasts; as the maths suggests, a few writers are booked more than once, topped by Raymond Chandler with four entries and Cormac McCarthy with five. Between those two, from The Big Sleep to The Road, is about where Gavron makes his pitch. We start with tight city shadows and the grind of investigation, then they shade into something more expansive and ominous, as the narrator’s obsession grows and he sets out for the north.

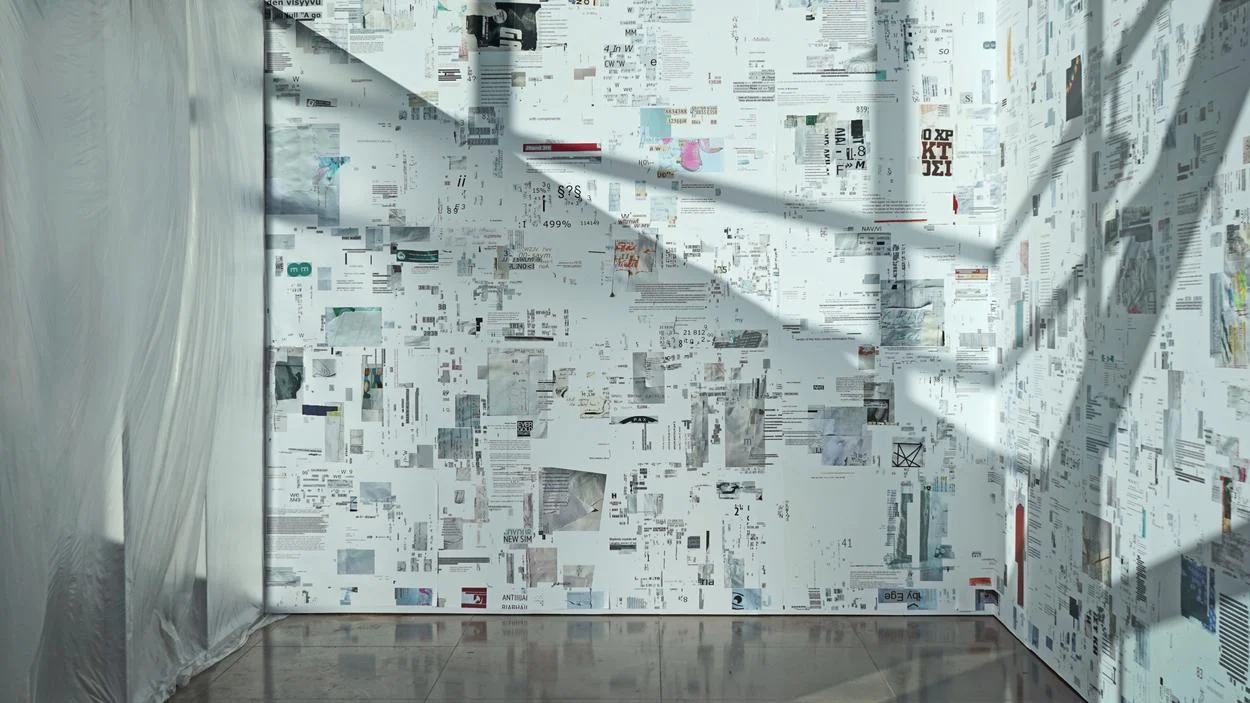

A collage needs to show its seams. When it yokes disparate pieces together, whether on a page or a canvas, its effect depends on playing off a new whole against an existing variety. So, when the artist Hannah Höch replaced Kaiser Wilhelm’s moustache with two wrestlers, she needed them both to fit and to look out of place; too much either way, and the image would be merely unchanged or destroyed. In between was the useful weirdness, the train of thought you could decode as humour, then satire, then political statement. The same is true of Gavron’s novella, where the use of collage might sound needless at first – ‘mostly use quotation’ sounds like decaf Oulipo – but it gradually forms an intelligent portrait of how detective stories work.

This is a genre that hangs on blanks and lacunae, the things that people don’t yet know. (If Philip Marlowe could just interview God, Chandler novels would be short.) In that sense, they’re stories of trying to listen: the investigator strains to pick out a clue, match his account to hers, track down a dingy address based on a name half-heard in a bar. In Felix Culpa, the early chapters are only partly ‘sourced’ from elsewhere, so Gavron may have tidied them up, and the connections do seem cogent:

Starts at the beginning with his pre-sentence report.

Accounts of his early relations with police.

Broke into a newsagent with two other juveniles and stole confectionary and cigarettes.

Age of eleven or twelve.

Living with his mother.

Much later, months into the voyage north, the narrator is delirious and hobbling and dressed in damp rags. When he spots a little farmhouse, he slips in and falls asleep.

Slept unquiet.

Saw faces, heard voices.

Thought the country was saying something to him.

Wind was trying to whisper something to me and I couldn’t make out what it was.

Something else like the faint fall of soft bare feet.

Looked up to see a little boy.

It’s as tricky for us to construe as it was for the narrator to think. The swing between grammatical persons – ‘me’, ‘I’ – and the apparition of ‘the little boy’ – a dream, a phantom, another writer’s creation – show a man losing his head, while straining to stitch his thoughts together.

Much of Felix Culpa remains elusive, as the incidental details of its backdrop are drowned in the dissonant buzz. Then again, in its ‘sources’, a gripping atmosphere is often conjured by what we’re not clearly told. (Who kills the chauffeur in The Big Sleep? What caused the apocalypse in The Road?) Gavron’s hero is a kind of obsessive journalist, and the white spaces between the paragraphs are doing steady, honest work. They conjure the grind and slow progress involved in making connections, digging for a story, when life is mortal and unideal. Like a Hannah Höch piece, Felix Culpa uses collage with impressive purpose. It refuses to give you a pleasant read. Non-compliance can be a sign of integrity, after all.